When I arrived back in Spokane last week, I came home to a package from Sitka National Historical Park. Inside were the following contents:

|

| My loot |

- A postcard from the supervisors

- The Most Striking of Objects: The Totem Poles of Sitka National Historical Park

- Carved History: The Totem Poles and House Posts of Sitka National Historical Park

- The Russian Bishop's House: Legacy of an Empire 1842

- For God & Tsar: A Brief History of Russian America 1741-1867

- A key-shaped thumb drive

It took me a while to figure out that the key was, indeed, a thumb drive, but when I plugged it into my laptop, it came up with folders upon folders of training documents, amounting to literally hundreds of pages of information.

Where to begin? I wondered.

I decided to start with totem poles, one of Sitka's most prominent tangible features. I read all the documents in the "Totem Poles" folder, and then spent the next 3 days taking notes on

The Most Striking of Objects, which actually contains a surprisingly thorough history of the topic.

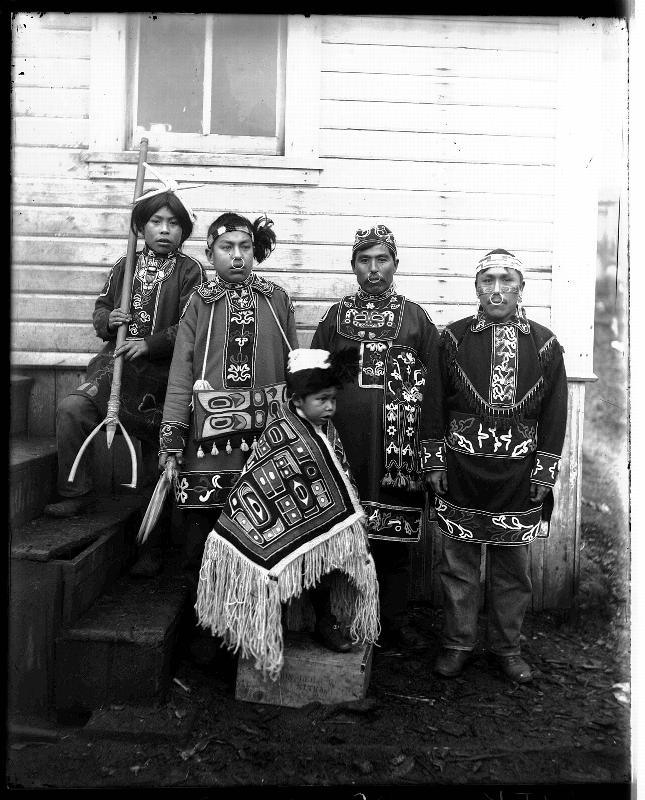

|

| NPS photo |

In order to understand totem poles, one must first have some knowledge of the Tlingit (pronounced "KLINK-it"), one of the most prosperous sedentary non-agricultural societies in the world. Reading up on the Tlingit totally brought me back to my anthropology classes in college, studying the works of Levi-Strauss and Boas, who contributed greatly to our modern understandings of Northwest indigenous groups.

What made Tlingit society so prosperous, though? Well, their villages contained multiple clans, each self-governed by a clan leader, with the dominant clan's leader ruling the entire village. This matrilineal society as a whole is divided into 2 moieties (descent groups), Eagle/Wolf and Raven. As such, Eagles can only marry Ravens and vice versa, with lineage being passed down through the mother (i.e. if the mother is Raven, her sons and daughters will also be Raven even though their father is Eagle). Pretty neat, huh?

So now we come to our totem poles. These first came about most likely as house posts, and then to represent clans, or families, in the villages, often presented at potlatches given by influential village members. The word comes from the Algonquin word "

ototeman," meaning "he is a relative of mine." There are 3 main types of poles:

- Crest poles: located in front of each clan house, facing the ocean, and identifies the family who lives there. These usually displayed the moiety affiliation and other animals associated with the clan.

- Memorial poles: Honor someone important or deceased; some hold the ashes of the deceased in a cavity in the back or on top of the pole. These were often plain in design with one figurehead on top.

- Legend poles: Record events or the history of a clan, often with multiples figures or designs throughout.

The design and placement of a pole can also have a bearing on its purpose. Some poles were designed to shame someone who failed to pay a debt or committed a crime; others might commemorate a significant event.

|

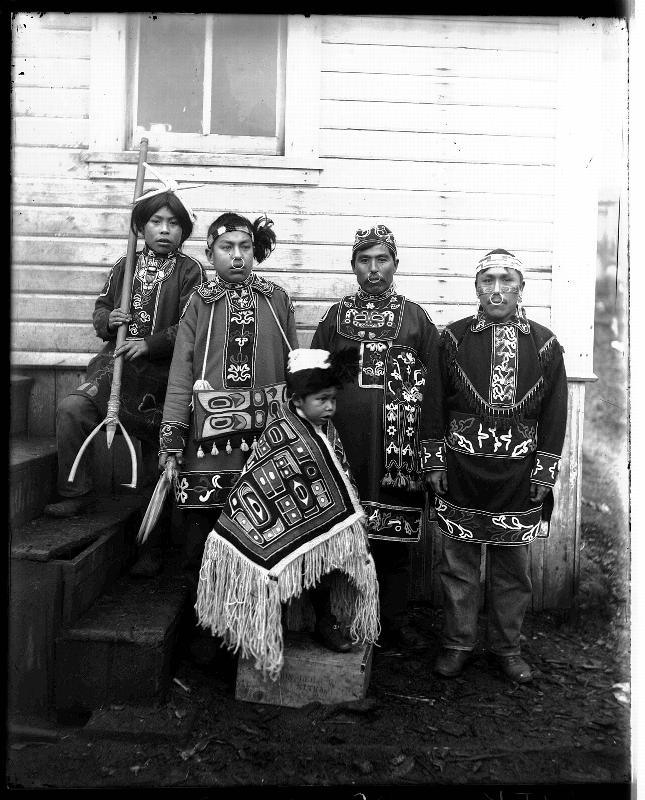

| NPS photo/E.W. Merrill |

Then of course, European contact happened. It started with the Russian fur traders in 1741 who discovered the abundance of sea otters around Alaska's southeastern islands. As the century progressed, British and later, American explorers also hopped on the bandwagon actively trading with the Tlingit -- and not only furs, but also alcohol and other foreign commodities, making way for the eventual acculturation and cultural borrowing of the indigenous communities.

Interestingly, aside from the introduction of new diseases and alcoholism into Tlingit society, the native groups gained some benefit from their commercial relationship with the Europeans. They began carving more totem poles, and even became capitalistic, trading with more remote native tribes and then selling to the Europeans at inflated prices.

In some ways, this worsened the economic disparity present in Tlingit society. Only higher ranked members traded with the Europeans, which further elevated their status, while lower-class villagers remained in their lower ranks. It wasn't until the "virgin soil epidemics," when new diseases were introduced, that the social statuses were evened out because of the population reduction (and hence opportunities for lower-status members to assume higher ranks).

|

| Those shifty Europeans... (NPS photo/E.W. Merrill) |

With the expansion of the fur trade and European presence in southeast Alaska came the missionaries. The only major attempt, however, was the Russian Orthodox Church, which met resistance from the Tlingit society. By this time, the Tlingits were already so prosperous, materialistic, and individualistic that they saw no benefit to converting to the Western ways, and continued about their business as usual.

After Alaska was purchased in 1867 however, American policies and missionaries became more predominant, and the native culture slowly began to wane. Alcoholism ran rampant, the fur trade industry gave way to commercial fishing as the sea otters were hunted out, and the native villagers went to work for fish canneries. In addition, shamans lost their credibility with their inability to cure the introduced diseases, causing a rift in native healing traditions and beliefs. With Christian missionary schools popping up like dandelions, totem poles became less significant because they were seen as heathen icons.

|

| A glimpse of Sitka at the turn of the century (NPS Photo) |

By this point, it's the 1890s and things are not going well for the Tlingit. So enter our hero, Governor John Brady. He actually had a pretty good relationship with the Tlingit, and was commissioned to collect totem poles for two upcoming World's Fairs, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and the Lewis & Clark Exposition in Portland in 1904. With these, he created elaborate displays of native culture in Alaska, spurring a renewed interest in tourism and homesteading on the Last Frontier.

After the World's Fairs in 1906, the totem poles were brought back to Sitka and placed in the government park, what is now Sitka National Historical Park (I told you it was the oldest federal park in Alaska, didn't I?). The poles were erected and arranged by one Elbridge W. Merrill, an eccentric local photographer who eventually became the park's caretaker. He arranged them to be aesthetically pleasing along the park's trail, and cared for them for years but refused to be employed and paid by the park service.

Interesting side note: at this point in 1918, an NPS ranger's

annual salary was a whopping $12 per year!

Well, eventually the park received more funding, with FDR's New Deal, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Works Progress Administration, allowing for better upkeep of the totem poles. They were re-carved in the 1940s, as most of them had rotted away and in 1972 the park was christened Sitka National Historical Park by Pres. Nixon, securing it slightly more adequate funding and providing federal protection of the totem poles and historic sites located within its boundaries.

So there you have it, the abbreviated history of Sitka's totem poles as interpreted by yours truly.

Up next, Russian tsars, bishops, and bloody battles!

.JPG)

.JPG)